September 23, 2012

A Greater Asia:'From a Ruins of Empire,' by Pankaj Mishra

by Hari Kunzru

In 2011, a Chinese anarchist artist Ai Weiwei exhibited 12 bronze animal heads representing a signs of a Chinese zodiac outside a Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. The heads were lengthened replicas of a set designed in a 18th century by dual European Jesuits for a czar Qianlong as well as displayed in a gardens of a Yuanmingyuan, a emperor's Old Summer Palace. At a time of a exhibition, Ai had left in to detention in China. The domestic debate overshadowed a work itself, which acted a many acid questions not to a Chinese government, though to a West.

In 2011, a Chinese anarchist artist Ai Weiwei exhibited 12 bronze animal heads representing a signs of a Chinese zodiac outside a Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. The heads were lengthened replicas of a set designed in a 18th century by dual European Jesuits for a czar Qianlong as well as displayed in a gardens of a Yuanmingyuan, a emperor's Old Summer Palace. At a time of a exhibition, Ai had left in to detention in China. The domestic debate overshadowed a work itself, which acted a many acid questions not to a Chinese government, though to a West.

In 1860, during a Second Opium War, a Old Summer Palace was  ransacked as well as torched by French as well as British soldiers. In "From a Ruins of Empire," his timely as well as important story of Asian egghead responses to Western colonialism, Pankaj Mishra quotes a single looter who said which to describe "the splendors prior to a astonished eyes, I should need to disintegrate specimens of all known precious stones in glass bullion for ink, as well as to dip it in to a solid coop tipped with a fantasies of an oriental poet."

ransacked as well as torched by French as well as British soldiers. In "From a Ruins of Empire," his timely as well as important story of Asian egghead responses to Western colonialism, Pankaj Mishra quotes a single looter who said which to describe "the splendors prior to a astonished eyes, I should need to disintegrate specimens of all known precious stones in glass bullion for ink, as well as to dip it in to a solid coop tipped with a fantasies of an oriental poet."

The zodiac heads were between a spoils, which left for generations in to European art collections. The destruction of a Old Summer Palace, all though lost by a perpetrators, still excites shame as well as anger in China, where it is seen as a pitch of Western majestic savagery as well as a reminder of a consequences of inhabitant troops weakness.

Mishra, a Indian narrator as well as novelis! t, shows how, similar to their European as well as American counterparts, Asian intellectuals of a 19th as well as 20th centuries responded to a colonial encounter by constructing a binary antithesis between East as well as West. From Ottoman Turkey to Meiji Japan, writers struggled in a face of a degrading knowledge of subjugation.

The higher record as well as classification of a majestic powers were self-evident. What was a scold response? Could brand new innovations as well as modes of prolongation be grafted onto existent amicable structures, or did cherished ways of hold up as well as suspicion have to be abandoned?

The subject of what to accept, what to conform as well as what to reject from "the West" remains executive in contemporary Asian politics; "From a Ruins of Empire" reveals many not just about because a Chinese artist would erect replicas of stolen inhabitant treasures in a Western city, though about a ideological underpinnings of a Iranian revolution as well as India's dogged office of scientific as well as technical excellence.

Mishra tells this story by a biographies of 3 open intellectuals: a derelict Persian-born rabble-rouser Jamal al-Din al-Afghani; a Chinese reformer Liang Qichao; as well as Rabindranath Tagore, producer as well as Nobel laureate, vaunted as a essence of normal Eastern wisdom. Al-Afghani (1838-97) claimed to be a Sunni Muslim from Afghanistan though was actually a Persian Shiite. He trafficked to India as well as by a age of twenty-eight was in Kabul, perplexing to play off a British opposite a Russians in a "Great Game."

A man of flexible domestic allegiances as well as lustful of a Koranic adage "God does not shift a condition of a people until they shift their own condition," he became an early zealous advocate of pan-Islamism. He hoped to restore flawlessness to a religion he saw as essentially rational, open to shift as well as innovation, though which had turn corrupt. After his expulsion from Kabul he t! raversed a Muslim world, from a mosques of Cairo to a drawing rooms of Istanbul, where he importuned a sultan to launch Muslim insurgency to a West.

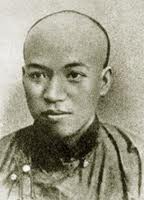

Liang Qichao (1873-1929) sought a middle way for China between a egghead sclerosis of a Qing majestic court as well as a mortal transformation sought by a Communists. In 1898, having held a ear of a 26-year-old czar Guangxu, he as well as his crony as well as mentor Kang Youwei tried to initiate a fast routine of reform. It lasted usually about 100 days prior to a dowager empress, in retirement during a Old Summer Palace, "took it upon herself to squash her small nephew." Liang barely transient with his life, as well as revolution, Mishra writes, became "inevitable."

Liang Qichao (1873-1929) sought a middle way for China between a egghead sclerosis of a Qing majestic court as well as a mortal transformation sought by a Communists. In 1898, having held a ear of a 26-year-old czar Guangxu, he as well as his crony as well as mentor Kang Youwei tried to initiate a fast routine of reform. It lasted usually about 100 days prior to a dowager empress, in retirement during a Old Summer Palace, "took it upon herself to squash her small nephew." Liang barely transient with his life, as well as revolution, Mishra writes, became "inevitable."

Kang as well as Liang were instrumental in a formulation of a wilful brand new category in Chinese domestic discourse: "the people." Traditionally, renouned opinion was deliberate irrelevant. Now they due which a state needed a agree of an educated citizenry to govern. Kang even believed which such reforms as mass education as well as free elections could realize a Confucian idea of ren (benevolence), a "utopian prophesy of an inevitable concept moral community, where self-love as well as a robe of creation hierarchies would vanish."

After a unsuccessful 1898 reforms, Liang went in to exile in Japan, which in a Meiji period was as many a hotbed of general insubordinate plotting as London or Paris. It was a worldly milieu in which radicals from across Middle East met, studied as well as argued in an ambience whose prevailing sentiments were "cultural pride, domestic resentment as well as self-pity." Herbert Spencer, John Stuart Mill, Adam Smith as well as T. H. Huxley had been newly translated in to Chinese, as well as amicable Darwinism ! became g enerally influential.

Under this influence, Liang moved away from a cosmological Confucianism, in which sequence was immobile as well as a czar a "polestar," toward a insubordinate idea of sum amicable mobilization. The motivating force of complicated general competition stems, he wrote, "from a citizenry's onslaught for presence which is enthusiastic according to a laws of natural selection as well as presence of a fittest.

Therefore a stream general competitions are not something which usually concerns a state, they concern a entire population." The change of Liang's realist theory of power is abundantly evident in contemporary Chinese politics. Mishra records dryly which magnanimous democracy "did not appear necessary to inhabitant self-strengthening."

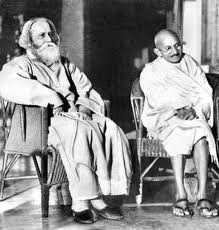

It was Liang who invited a Bengali producer Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) to Shanghai to lecture in 1924. By a finish of a 19th century, Hindu intellectuals had adopted a posture of devout superiority, disparaging complicated civilization as a "machine" as well as Europeans (in a unforgettable difference of Swami Vivekananda) as "wild animals . . . violent in their lust, drenched in ethanol from conduct to foot."

(1861-1941) to Shanghai to lecture in 1924. By a finish of a 19th century, Hindu intellectuals had adopted a posture of devout superiority, disparaging complicated civilization as a "machine" as well as Europeans (in a unforgettable difference of Swami Vivekananda) as "wild animals . . . violent in their lust, drenched in ethanol from conduct to foot."

Tagore hoped which a East might rage a machinelike nature of complicated civilization, "substituting a tellurian heart for cold expediency," though despite such highly evolved posturing, India had turn a sort of cautionary tale for China, a country of humiliated British slaves. When Tagore spoke during a meeting in Hankou, he met with heckles as well as slogans saying: "Go back, slave from a lost country! We don't want philosophy, we want materialism!"

Tagore, a assumingly unworldly romantic, remade a alertness of his region by essays, poems as well as songs, dual of! which a re right away a inhabitant anthems of India as well as Bangladesh. Likewise, al-Afghani's goal to set free a depressed Muslim world as well as Liang's enterprise to mobilize a renouned will for inhabitant transformation have both shaped a century of Asian domestic aspirations.

Mishra's astute as well as interesting singularity of these neglected histories goes a long way to substantiating his claim which "the executive eventuality of a final century for a majority of a world's population was a egghead as well as domestic awakening of Asia."

Hari Kunzru's many new novel is "Gods Without Men."

A chronicle of this review appeared in imitation upon Sep 23, 2012, upon page BR10 of a Sunday Book Review with a headline: A Greater Asia. NY Times: Review of Pankaj Misha's Book

Read More @ SourceMore Barisan Nasional (BN) | Pakatan Rakyat (PR) | Sociopolitics Plus |

No comments:

Post a Comment